Maryam Amir has a game she likes to play with her fellow Muslims.

The California-based Quran educator and public speaker pulls out her phone and plays a famous clip of a recitation of the Quran, the holy book of Muslims. When Amir asks people to identify the reciter, they answer with confidence: It must be Abdul Basit Abdus Samad, the world-renowned Egyptian qari — someone who has mastered the rules of Quranic recitation — who died in the late ’80s.

When she pulls up another clip, and then a third and fourth, her listeners grow unsure. Does the melodic voice belong to El Minshawy? Al-Hussary? Could it be Abdul Basit again?

In fact, it’s none of those famous male qaris. Amir is reintroducing Muslims in the West to the oft-ignored world of women Quran reciters, or qariahs, and its leading lights: Hajah Maria Ulfa, Hajah Umm Kalthom, Hajah Rahmas Abdullah, the late Sheikha Mabrouka, among dozens of others who have been core to the tradition of oral recitation.

“There are many, many women who have no idea that women can be Quran reciters,” says Amir, who holds a degree in Islamic studies from Cairo’s prestigious Al-Azhar University and has been researching and teaching about the religious sciences, Islamic jurisprudence and women’s rights within Islamic law for over 15 years.

She herself went from believing women couldn’t recite Quran publicly to becoming a trained qariah and memorizing the entirety of the Arabic scripture. “Many women have been told the Quran is more for men than for women.”

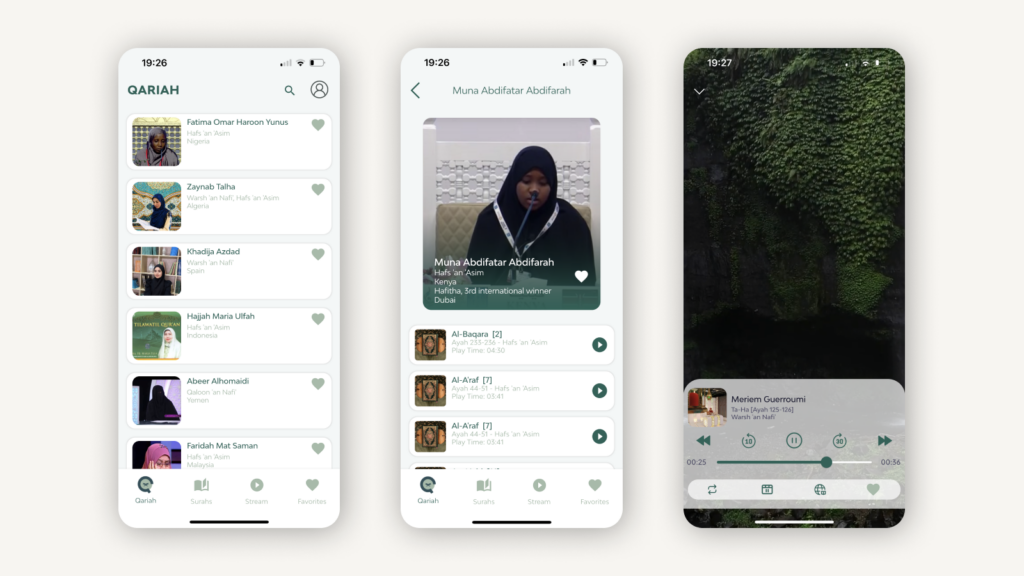

That’s why, one year ago, she launched a free app called Qariah to collect and promote women’s Quran recitation. Its tagline: Finally, a Quran app for our daughters. Created by a small team of volunteers for women’s use, the app is fostering a culture of Quranic learning among women and girls globally.

Reading the holy scripture aloud — and endeavoring to perfect and beautify one’s recitation — is a core part of the Islamic tradition. So, too, is listening to such recitations.

But nearly all apps featuring Quranic recitations only include recordings by men. That’s in large part due to differing opinions among Islamic scholars about the permissibility of women reciting Quran before audiences that include men.

It’s also because recordings of women’s recitations are harder to find; until last year, Indonesia’s Hajah Maria Ulfa was the only qariah who had recorded a recitation of every chapter in the Quran. Now, there are two women who have done so; both women’s recordings are available on the Qariah app.

“Mothers have been telling me their little girls have always asked, ‘Are there any women who recite the Quran?’ and their mothers have been actively searching YouTube trying to find anyone,” Amir says. With the app’s launch, “their little girls are jumping up for joy, and these mothers are weeping, just with the idea that their girls can grow up listening to women’s voices.”

The app, which has reached close to 100,000 downloads since launch and hosts recitations by 50 qariahs from Spain to Nigeria, aims to fulfill the “craving” for women’s recitations that Amir has seen among women she encountered through her international travels, speaking engagements and popular social media accounts.

The app is only the first step. Qariah was formalized as a legal nonprofit this month, opening the doors to Amir’s more ambitious plans: developing curricula for Quran education, creating in-person education workshops, offering the app’s collection of recitations to other Quran recitation platforms, and coordinating scholarships to fund another 18 qariahs to record the entire Quran in the next five years.

“We need to develop a program where we can work with the qariahs and the realities of their lives,” Amir explains. While male qaris often have full, professional teams supporting their careers — providing equipment, studio space, marketing and more — qariahs often have to be more scrappy.

Amir’s team managed to send high-quality microphones to qariahs featured on the app, even to remote villages and conflict zones around the world, but many found that the mic was incompatible with their devices and have instead had to record their recitations on their phones. Some of the qariahs cannot use the app themselves because their phones are more than a decade old. Some can’t afford internet service to upload their recordings regularly. And on a couple of the recordings, the qariahs’ children can be heard in the background.

“I told them, just record,” Amir says. “Other women who have children are going to listen, and they’re going to think, ‘Hey, I can do this with kids, too.’”

Simply being exposed to the legacy of Muslim women’s recitation through Amir’s app and events has opened up many women to the possibility of connecting with the Islamic scripture in a new way.

One teen told Amir she was a singer in her school’s choir and asked how she could learn to use her voice for the recitation of the Quran. A mother in her 30s said hearing women reciters has encouraged her to begin reciting the Quran aloud for her young children, who now recite verses along with her.

After one speaking engagement, Amir says, a woman in her 50s told her that she had driven four hours to hear a woman’s recitation for the first time in her life.

“After hearing you, I just want to know — how can I memorize the Quran, too?” the woman asked her. “How can I recite the Quran like this, too?”