When Lydia Eccles moved into her fifth-floor apartment in Boston’s Kenmore Square in 2015, she nearly cried with relief. She had spent the past nine months couch-surfing and looking desperately for housing, having lost her previous artist loft to development — like every other home Eccles had lived in for nearly 25 years in Boston.

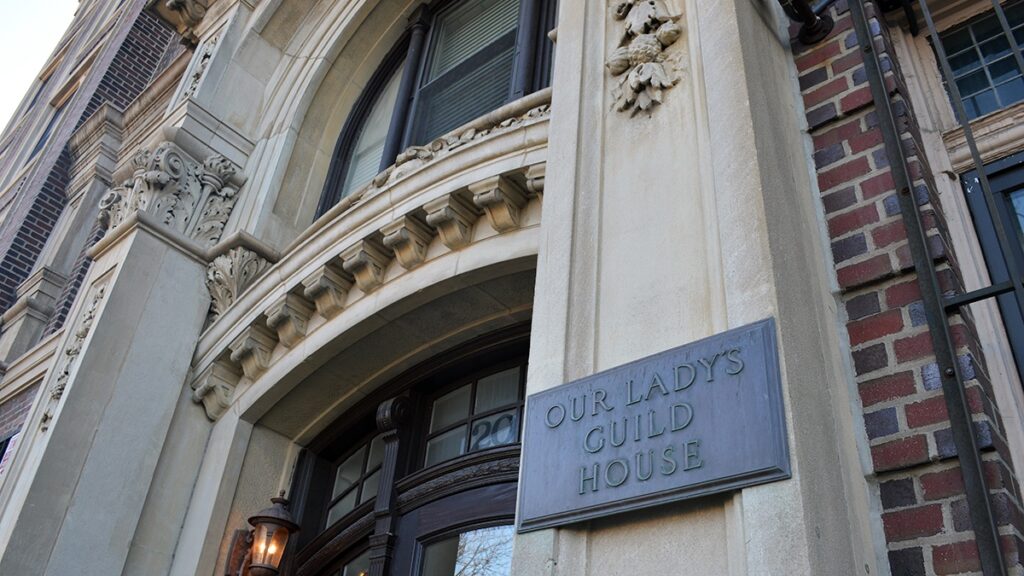

She immediately fell in love with the unique charm of the charitable women’s affordable rooming house. Managed by a small order of Catholic nuns in Connecticut, Our Lady’s Guild House (OLGH) was home to dozens of low-income seniors, some of whom had lived there as long as three decades.

“It was like time-traveling in this building, it was so idyllic and intimate,” recalls Eccles, a 68-year-old conceptual artist and accountant. Founded in 1947, Our Lady’s Guild House offered 137 affordable single-occupancy rooms for women in a spiritual, communal environment. In Boston’s tight housing crunch, the building felt anachronistic.

“I really liked seeing women of all ages living together. I really thought I had found a kind place.”

But the same housing crisis that had chased Eccles from apartment to apartment since 1995 followed her here, too: Every single neighbor she met would receive notice to leave the building.

“They were all being forced out,” she says. In total, 81 women — nearly all elderly — were displaced from their homes, she says, making way for higher-paying, short-term tenants who would draw profit for the nuns’ dying order.

After receiving her own notice, Eccles joined her neighbors in complaining to the Massachusetts Attorney General in 2018 against OLGH for discriminating against older and disabled tenants. Last week, a civil rights investigation by the state resulted in the building’s managers being fined for a slew of illegal “no fault” evictions as well as its discriminatory attempts to push out elderly and disabled long-term tenants. The state also secured an agreement to sell the building to local nonprofits and maintain its mission to provide affordable housing.

While the decision is welcomed by some housing activists, the building’s longtime residents say the settlement is insufficient – and more concerningly, could lead to a loss of a rare form of affordable housing that provided single women with both independence and community.

Prophetic to profit-motivated

Judy Burnette, a retired educator, has lived at OLGH since 2008. At the time, after leaving an unsafe housing arrangement, Burnette’s rent was around $400 monthly.

For months, she struggled to find options that cost less than $1,200 monthly. Securing a room at the Guild House lifted “a massive weight” from her shoulders, she says

Boston has long had one of America’s most expensive rental markets. The crisis is deepening rapidly: From 2009 to 2017, Northeastern University found that the average monthly rent in inner Boston rose by about 55% to $2,874.

For decades, Our Lady’s Guild House served as a haven in the heart of the city for single women of all ages, many of whom were low-income, retired, disabled, widowed or fleeing abuse.

The brick building’s antique brass mail boxes, detailed moldings, Catholic art and statuary underscore that heritage as a historic, spiritual sanctuary in the heart of a city undergoing a major housing and eviction crisis.

“Spirituality is the only source of opposition to sheer economic calculation, I think.”

OLGH’s story goes back to 1946, when the Archdiocese of Boston purchased the Hotel Gralyn to convert into a lodging home for Catholic women visiting the city. A “good portion” of the building was also expected to permanently house Catholic women, according to a Boston Globe article published then. “The house will become an active part of the Catholic life of the city,” the Globe wrote.

Then-Archbishop Richard Cushing created a Massachusetts nonprofit corporation and gifted the building to it. Cushing entrusted ownership of the lodging home to the Daughters of Mary of the Immaculate Conception, an order of nuns in Connecticut, charging them with operating the lodging house as a ministry.

OLGH soon opened as a 120-unit single room occupancy rooming house run by the Daughters of Mary, with nuns staffing and living in the rooming houses, cooking communal resident meals and leading daily mass services. The Guild House’s stated mission was to “provide safe and affordable housing for single women, working women, retired women or students,” without seeking profit.

Like many residents, Eccles is not Catholic herself. But having experienced homelessness, she has long appreciated religious movements’ ability to provide a social safety net wherever governments and corporations fail.

“Spirituality is the only source of opposition to sheer economic calculation, I think,” she says.

But over the next six decades, Daughters of Mary dwindled from about 200 sisters to about 20. The OLGH’s ministry shifted accordingly. Communal meals were no longer provided, units were opened to non-Catholic tenants and the order eventually began contracting management of its charitable properties to outside organizations.

In 2007, the Daughters of Mary’s mother superior hired Boston-area commercial real estate firm Marc Roos Realty to manage the building for the aging nuns. Under Roos, management shifted toward listing units as Airbnbs and attracting international college students for higher-paying, short-term leases.

Monthly rents were first raised by $100, a serious blow to residents on a fixed income, and Roos began advertising open units for $825. Tenants were informed of a new residency time limit and given a two year-deadline to leave.

The news devastated the elderly residents, activists say. “They took these women, ripped them from their home and traumatized them,” says Eccles. Her 84-year-old friend developed stress-related shingles. Another woman had a psychotic breakdown. One reportedly committed suicide within weeks. “These were healthy, happy women living out their oldest days amongst their friends.”

OLGH began turning away potential renters based on age. One OLGH lease made it explicit, stating that all tenants must be “independent,” “self sufficient,” and “physically and mentally capable” of cooking and cleaning.

“Any current residents who are NOT independent may be asked to leave,” the lease read. “This sometimes may occur when age is upon a person.”

The building began asking new tenants for four months of rent up front, and to show proof of enrollment in school or employment pay stubs.

“They took these women, ripped them from their home and traumatized them. These were healthy, happy women living out their oldest days amongst their friends.”

Boston census data from 2009-2010 shows that about 70% of the building’s residents were over 40 years of age; about 50% were over 50. By 2019, per a resident survey by Eccles, the proportion of residents over 40 years of age had dropped sharply to 5%. Residents over 50 years comprised less than 2%

All eight of the remaining senior residents were facing eviction under the new two-year residency time limit.

Both nuns and local Catholic leadership, meanwhile, did not respond to residents’ and activists’ requests and grievances. A group bussed to Connecticut to request a meeting with the order’s mother superior, to no success. (Neither the order nor Roos have responded to requests to comment for this story.)

When residents saw that the OLGH’s website had begun to explicitly describe the building as open to “short-term” tenants “between the ages of 18 and 50 years old” who attend school or work locally, they took their landlords to court.

The Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination has since found probable cause for age- and disability-related discrimination in five separate tenants’ cases.

“We really thought we were holding them accountable and getting justice,” says Eccles. “But they’re slipping away in this transaction.”

After years of dragging its feet, OLGH agreed last week to sell to Boston-based affordable housing developers, the Fenway Community Development Corporation and the Archdiocese-affiliated Planning Office for Urban Affairs. The buyers say the property will become “100% permanent affordable housing.”

But the building’s remaining longtime residents say the Catholic order should have been required to donate the property to the nonprofits at no cost.

Losing options

Eccles, who along with five other women were the lone holdouts still resisting eviction from OLGH, believes the sale of the building actually violates the state’s public charities dissolution law.

In Massachusetts, if it is feasible for a dissolving charity’s assets to continue to serve its original mission, then the charity must donate its net assets to other nonprofits with missions as close as possible to the asset’s original purpose. That’s what the Little Sisters of Poor did in 2019, when the group of Catholic nuns withdrew from a low-income seniors home in nearby Somerville. The Little Sisters of the Poor then transferred the property to the Visiting Nurse Foundation, which agreed to retain the residents through the transition.

If the original purpose cannot be continued, under state law, the dissolving charity must sell its property at fair market value before donating the cash to a Massachusetts charity with a similar goal.

But the Daughters of Mary chose another route with OLGH. Tenants accuse management of circumventing dissolution by changing its charitable mission to providing short-term student housing at market rates, rather than its historic purpose of providing affordable housing to women of all ages for short- and long-term stays with no profit.

Instead, the evicted tenants allege, the nuns sought to sell the building on the open market to a private developer to channel profits to their dying religious order.

Through the settlement with the state attorney general’s office, they’ve been pushed to sell to nonprofits instead. But residents believe the property ought to have been transferred without a price tag — and that its full, original mission as a single-room occupancy building must be maintained.

As a single-room occupancy (SRO) building, tenants at OLGH had private bedrooms and shared communal kitchens, bathrooms and lounges.

Under the new sale, the building will be preserved as affordable housing. But the nonprofits who will soon take ownership of the building have no intention of maintaining an SRO, as Fenway CDC’s Richard Giordano indicated to the Boston Business Journal.

“Right now, unfortunately, it’s become a de facto dormitory,” Giordano said. “It’s certainly going to be affordable housing and it certainly won’t be a dorm, de facto or otherwise.”

Residents believe the new affordable housing development, if the building is gutted and converted into apartments, would eliminate at least 50 units and many common spaces. And the property’s dorm-like nature made it particularly affordable for tenants — at roughly a third the cost of the average price of a Boston-area studio. It was also a draw to single women looking for privacy and independence, while also offering a community of residents.

“For single women, all these things are precious. That you’re safe and secure. That you still have independence. That nobody tells you when to come and go. And that you can afford it.”

For Burnette, being able to pool money for groceries together with other residents and eat together in the kitchen, but also being able to go into her room and close the door, made OLGH unlike most other housing options in the city, she says.

“For single women, all these things are precious,” Burnette says. “That you’re safe and secure. That you still have independence. That nobody tells you when to come and go. And that you can afford it.”

But renting out single bedrooms with common lounges, kitchens and bathrooms is a far less profitable model than offering studio and one-bedroom apartments, and setting some of them aside as affordable housing.

Some cities are beginning to reconsider SROs — once central to urban life, but much maligned in the post-World War II era — as a solution to homelessness, seeking to preserve existing SROs before their owners convert them into luxury condos. But in Boston’s few remaining SROs, residents are receiving eviction notices year after year as their owners sell to developers in multi-million dollar deals.

It’s a crisis that is displacing hundreds of single seniors around the country, who have nowhere else to go but shelters and the streets.

“There is a dire need in Boston for safe, affordable housing for women who cannot afford a place to live other than SRO housing,” says Burnette. Even with this affordable housing victory, activists say, that may have been lost.