Break their lineage, break their roots, break their connections and break their origins.

That, according to one Chinese state official, has been the aim of Beijing’s ongoing campaign to repress millions of China’s minority Uyghurs, an ethnically Turkic and mostly-Muslim minority that is facing what human rights experts call a genocide.

Through the work of rights activists, journalists and members of the global Uyghur diaspora, countless crimes have been exposed: Mass detention, enforced disappearances, mass surveillance, forced labor, forced sterilization, organ harvesting, sexual violence, and the attempted erasure of the Uyghur people’s language, history and culture.

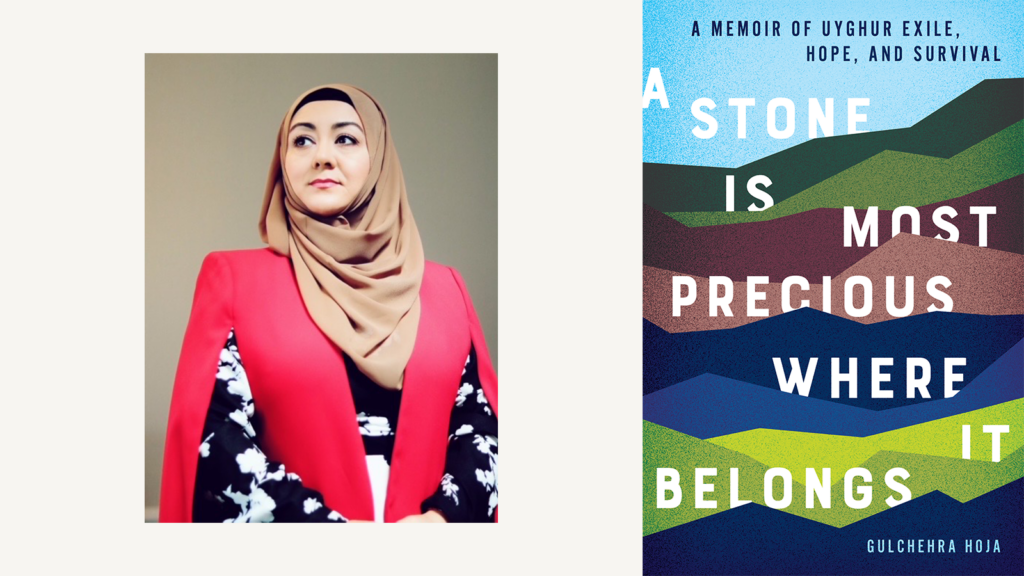

One unwavering voice exposing these atrocities is that of Gulchehra Hoja, a 49-year-old Uyghur activist and journalist living in Washington, D.C. For years, she has been at the forefront of keeping the world informed of the repression in her homeland, breaking major news stories as a reporter with Radio Free Asia.

Like many Uyghurs living abroad in exile, her own family has fallen victim to the systematic repression her reporting has revealed. But she’s also been uniquely targeted: In retaliation for her work, two dozen of her family members were arrested in one night, and she herself has been put on China’s “most wanted” list. “The identity of the entire Uyghur people is being wiped out, and their existence is threatened today,” Hoja says. Being a Uyghur journalist living outside of China means she bears a heavy responsibility. “This is not a regular job. This is a duty to help people, to be a voice for the entire voiceless people, and also keeping our culture and language alive.”

Hoja spoke to Analyst News about her new memoir, A Stone Is Most Precious Where It Belongs, which details her remarkable journey from a bright-eyed television personality to an activist-journalist fighting for her people and her family. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What inspired you to share your personal journey with the world?

In recent years, the world is beginning to learn about what happened to the Uyghur people in my homeland of East Turkistan. But unfortunately, they learned about us through the genocide. It’s a shame for the Uyghur people to be recognized as victims of genocide, as victims of Chinese human rights abuses. So I wanted to show Uyghur history and our culture and art.

That was my point in writing this book, and why I chose this title. We Uyghurs have this saying, “Tash chüshkän yeridä äziz.” My father used to tell me this, that even a stone is precious where it belongs. I live through the deep value of this proverb, which is often applied to Uyghurs who are separated from their family, their birth place, their homeland.

You came to the United States to work when you were 28 years old, unable to speak the language. Shortly after, you found out that your grandmother had passed away and your dad had had a stroke. What kept you going despite so many challenges?

I was very emotional and even confused. Some days I would wake up and just regret what I did. But then the next day, I would stay very strong and be reminded that this is the right choice for me. Before I came to the U.S., I was a host for a children’s program for Chinese state television, called Xinjiang TV. I was a fairy tale storyteller for the Uyghur children.

But since I started working as a Uyghur journalist at Radio Free Asia, I started to tell the real story about Uyghurs, which is full of pain. The human rights issues, abuses — all that is happening for real, and people are expecting us to tell their story to the world because they are voiceless. The people’s wish and trust motivate me to stay strong and be the voice for those who don’t have a free voice. So, I continue my work as a duty.

In 2018, 24 members of your family were detained by the Chinese government. The next day, you made the choice to write that government an open letter. What was going through your mind?

I was very angry. I was furious. At the same time, I was very much feeling guilty that my family is paying for what I’m doing as a journalist.

Before my 24 family members were arrested, my only brother was arrested. Two months earlier, in September 2017, the Chinese government started giving me this warning to be silent. And I didn’t. Because I didn’t stop reporting, they took all of my family members.

The human rights issues, abuses — all that is happening for real, and people are expecting us to tell their story to the world because they are voiceless.

I felt like it’s my responsibility to help them — being a U.S. citizen, a human being, a daughter of my family, that’s my duty. Only I could do that. I told my husband that I’m going to go into the Chinese embassy, and I will tell them, “Whatever you want, it’s with me. My family doesn’t have anything to do with my job. So free my family.” I didn’t think about anything else. I didn’t think about my children. And my husband says, “If you return there, there will be 25 people I need to help.”

Even if I go back, they will not free my family, and they will do whatever they do to all of us. Instead, I have the chance here to help all of my people and all of my relatives. That’s why we have to continue, and so I started with this letter to the Chinese embassy and the U.S. government.

In 2021, the U.S. determined that China was likely committing a genocide and crimes against humanity against Uyghurs. Do you feel the U.N. is lacking in an immediate and urgent response?

Everyone knows what is going on in the Uyghur homeland. With Xi Jinping’s “no mercy” policy, what Uyghurs are facing today is genocide in every aspect of their lives. Many countries recognize what the Chinese government is doing to the Uyghur people. They all call it a genocide. When you recognize China’s crimes as a genocide or as crimes against humanity, then every government, including the U.N., must take strong action to stop it.

We’ve been reporting on the Chinese government’s heinous crimes in the Uyghur region already for seven years. But none of those countries or the U.N. take action. So there’s a huge responsibility, not only for the countries’ governments or the U.N., but for all of those who have a very strong beneficial relationship with the Chinese government to take strong action to stop it. We are witnessing and allowing this genocide to happen and for history to repeat itself. This is actually a human tragedy for the whole world, for the whole of humanity.

It’s currently Women’s History Month. What message do you want to share with other women today?

Women are the biggest victims of human rights crises, and Uyghur women today don’t have a choice as to what language they want to speak and what they want to wear. Even their kids are forcibly separated from them. And they’re being used as forced labor slaves and forced marriages are happening. Forced sterilization, rape, organ harvesting and murder is happening to them.

We Uyghur women are just like other women: we have feelings, we have heart, we have love, we have beliefs. Our sisters, our mothers, our daughters — please be aware of what’s happening to other women, other sisters, around you. We have to help each other, because we understand each other more.

After you learn about these human tragedies happening in my country, you have the duty, the responsibility, to stop this genocide.

I have been talking to 15 women camp survivors. They had a chance to leave the concentration camp alive because they were married to foreigners or they had dual citizenship. After they left, even though they’ve been abused, mentally, physically and sexually, they are standing up for other women who are still suffering in Chinese internment camps. Please listen to these camp survivors’ experiences and stories so you can understand more.

How can individuals take action to help the Uyghur people?

After you learn about these human tragedies happening in my country, you have the duty, the responsibility, to stop this genocide.

Check what you are buying right now. Maybe what you’re wearing is produced by the Chinese government using our people as slaves. When you go to the beauty salon to buy wigs, maybe it’s from my cousin’s hair that was cut in the concentration camp. When you’re wearing a cotton shirt, remember that 90% of cotton [produced in China] is coming from the Uyghur region. So when you purchase something, you actually have to think about other people. There may be human blood stains on those products.

Push your government to do something to stop this genocide. Write letters to the media. Even just share the news to spread awareness.